Pete Seeger

Pete Seeger | |

|---|---|

Seeger playing the banjo in 1955 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Peter Seeger |

| Born | May 3, 1919 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | January 27, 2014 (aged 94) New York City, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | Pete Seeger discography |

| Years active | 1939–2013 |

| Labels | |

| Spouse | Toshi Aline Oht |

| Military career | |

| Branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 |

| Rank | Corporal |

| Unit | United States Army Band |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

| Awards | |

| Signature |  |

Peter Seeger (May 3, 1919 – January 27, 2014) was an American folk singer-songwriter, musician and social activist. He was a fixture on nationwide radio in the 1940s, and had a string of hit records during the early 1950s as a member of The Weavers, notably their recording of Lead Belly's "Goodnight, Irene," which topped the charts for 14 weeks in 1950. Members of the Weavers were blacklisted during the McCarthy Era. In the 1960s, Seeger re-emerged on the public scene as a prominent singer of protest music in support of international disarmament, civil rights, counterculture, workers' rights, and environmental causes.

A prolific songwriter, his best-known songs include "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?" (with additional lyrics by Joe Hickerson), "If I Had a Hammer (The Hammer Song)" (with Lee Hays of the Weavers), "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine" (also with Hays), and "Turn! Turn! Turn! (To Everything There Is a Season)", which have been recorded by many artists both in and outside the folk revival movement. "Flowers" was a hit recording for The Kingston Trio (1962); Marlene Dietrich, who recorded it in English, German and French (1962); and Johnny Rivers (1965). "If I Had a Hammer" was a hit for Peter, Paul and Mary (1962) and Trini Lopez (1963) while The Byrds had a number one hit with "Turn! Turn! Turn!" in 1965.

Seeger was one of the folk singers responsible for popularizing the spiritual "We Shall Overcome" (also recorded by Joan Baez and many other singer-activists), which became the acknowledged anthem of the civil rights movement, soon after folk singer and activist Guy Carawan introduced it at the founding meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1960. In the PBS American Masters episode "Pete Seeger: The Power of Song", Seeger said it was he who changed the lyric from the traditional "We will overcome" to the more singable "We shall overcome".

Early years

[edit]Seeger was born on May 3, 1919, at the French Hospital, in New York City.[1] His family, which Seeger called "enormously Christian, in the Puritan, Calvinist New England tradition",[2] traced its genealogy back over 200 years. A paternal ancestor, Karl Ludwig Seeger, a physician from Württemberg, Germany, had emigrated to America during the American Revolution and married into the old New England family of Parsons in the 1780s.[3]

Seeger's father, the Harvard-trained composer and musicologist[4] Charles Louis Seeger Jr., was born in Mexico City, Mexico, to American parents. Charles established the first musicology curriculum in the United States at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1913; helped found the American Musicological Society; and was a key founder of the academic discipline of ethnomusicology. Pete's mother, Constance de Clyver Seeger (née Edson), raised in Tunisia and trained at the Paris Conservatory of Music, was a concert violinist and later a teacher at the Juilliard School.[5]

In 1912, his father, Charles Seeger, was hired to establish the music department at the University of California, Berkeley, but was forced to resign in 1918 because of his outspoken pacifism during World War I.[6] Charles and Constance moved back east, making Charles's parents' estate in Patterson, New York, about 50 miles north of New York City, their base of operations. When baby Pete was eighteen months old, they set out with him and his two older brothers in a homemade trailer to bring musical uplift to the working people in the American South.[7] Upon their return, Constance taught violin and Charles taught composition at the New York Institute of Musical Art (later Juilliard), whose president, family friend Frank Damrosch, was Constance's adoptive "uncle". Charles also taught part-time at the New School for Social Research. Career and money tensions led to quarrels and reconciliations, but when Charles discovered Constance had opened a secret bank account in her own name, they separated, and Charles took custody of their three sons.[8] Beginning in 1936, Charles held various administrative positions in the federal government's Farm Resettlement program, the WPA's Federal Music Project (1938–1940) and the wartime Pan American Union. After World War II, he taught ethnomusicology at the University of California, Berkeley, and Yale University.[9][10]

Charles and Constance divorced when Pete was seven and in 1932 Charles married his composition student and assistant, Ruth Crawford, now considered by many to be one of the most important modernist composers of the 20th century.[11] Deeply interested in folk music, Ruth had contributed musical arrangements to Carl Sandburg's extremely influential folk song anthology, the American Songbag (1927), and later created significant original settings for eight of Sandburg's poems.[12] Pete's eldest brother, Charles Seeger III, was a radio astronomer, and his next older brother, John Seeger, taught in the 1950s at the Dalton School in Manhattan and was the principal from 1960 to 1976 at Fieldston Lower School in the Bronx.[13] Pete's uncle, Alan Seeger, a noted American war poet ("I Have a Rendezvous with Death"), had been one of the first American soldiers to be killed in World War I. All four of Pete's half-siblings from his father's second marriage—Margaret (Peggy), Mike, Barbara, and Penelope (Penny)—became folk singers. Peggy Seeger, a well-known performer in her own right, married British folk singer and activist Ewan MacColl. Mike Seeger was a founder of the New Lost City Ramblers, one of whose members, John Cohen, married Pete's half-sister Penny, also a talented singer, who died young. Barbara Seeger joined her siblings in recording folk songs for children. In 1935, Pete attended Camp Rising Sun, an international leadership camp held every summer in upstate New York, which influenced his life's work. His final visit occurred in 2012.[citation needed]

Career

[edit]Early work

[edit]

At four, Seeger was sent away to boarding school, but came home two years later when his parents learned the school had failed to inform them he had contracted scarlet fever.[14] He attended first and second grades in Nyack, New York, where his mother lived, before entering boarding school in Ridgefield, Connecticut.[15] Despite being classical musicians, his parents did not press him to play an instrument. On his own, the otherwise bookish and withdrawn boy gravitated to the ukulele, becoming adept at entertaining his classmates with it while laying the basis for his subsequent remarkable audience rapport. At thirteen, Seeger enrolled in the Avon Old Farms School in Avon, Connecticut, from which he graduated in 1936. He was selected to attend Camp Rising Sun, the George E. Jonas Foundation's international summer leadership program. During the summer of 1936, while traveling with his father and stepmother, Pete heard the five-string banjo for the first time at the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in western North Carolina near Asheville, organized by local folklorist, lecturer, and traditional music performer Bascom Lamar Lunsford, whom Charles Seeger had hired for Farm Resettlement music projects.[16] The festival took place in a covered baseball field. There the Seegers:

watched square-dance teams from Bear Wallow, Happy Hollow, Cane Creek, Spooks Branch, Cheoah Valley, Bull Creek, and Soco Gap; heard the five-string banjo player Samantha Bumgarner; and family string bands, including a group of Indians from the Cherokee reservation who played string instruments and sang ballads. They wandered among the crowds who camped out at the edge of the field, hearing music being made there as well. As Lunsford's daughter would later recall, those country people "held the riches that Dad had discovered. They could sing, fiddle, pick the banjos, and guitars with traditional grace and style found nowhere else but deep in the mountains. I can still hear those haunting melodies drift over the ball park."[17]

For the Seegers, experiencing the beauty of this music firsthand was a "conversion experience". Pete was deeply affected and, after learning basic strokes from Lunsford, spent much of the next four years trying to master the five-string banjo.[17] The teenage Seeger also sometimes accompanied his parents to regular Saturday evening gatherings at the Greenwich Village loft of painter and art teacher Thomas Hart Benton and his wife Rita. Benton, a lover of Americana, played "Cindy" and "Old Joe Clark" with his students Charlie and Jackson Pollock; friends from the "hillbilly" recording industry; and avant-garde composers Carl Ruggles and Henry Cowell. It was at one of Benton's parties that Pete heard "John Henry" for the first time.[18]

Seeger enrolled at Harvard College on a partial scholarship, but as he became increasingly involved with politics and folk music, his grades suffered and he lost his scholarship. He dropped out of college in 1938.[19] He dreamed of a career in journalism and took courses in art as well. His first musical gig was leading students in folk singing at the Dalton School, where his aunt was principal. He polished his performance skills during a summer stint of touring New York state with the Vagabond Puppeteers (Jerry Oberwager, 22; Mary Wallace, 22; and Harriet Holtzman, 23), a traveling puppet theater "inspired by rural education campaigns of post-revolutionary Mexico".[20] One of their shows coincided with a strike by dairy farmers. The group reprised its act in October in New York City. An article in the October 2, 1939, Daily Worker reported on the Puppeteers' six-week tour this way:

During the entire trip the group never ate once in a restaurant. They slept out at night under the stars and cooked their own meals in the open, very often they were the guests of farmers. At rural affairs and union meetings, the farm women would bring "suppers" and would vie with each other to see who could feed the troupe most, and after the affair the farmers would have earnest discussions about who would have the honor of taking them home for the night.

"They fed us too well", the girls reported. "And we could live the entire winter just by taking advantage of all the offers to spend a week on the farm".

In the farmers' homes they talked about politics and the farmers' problems, about antisemitism and Unionism, about war and peace and social security—"and always", the puppeteers report, "the farmers wanted to know what can be done to create a stronger unity between themselves and city workers". They felt the need of this more strongly than ever before, and the support of the CIO in their milk strike has given them a new understanding and a new respect for the power that lies in solidarity. One summer has convinced us that a minimum of organized effort on the part of city organizations—unions, consumers' bodies, the American Labor Party and similar groups—can not only reach the farmers but weld them into a pretty solid front with city folks that will be one of the best guarantees for progress.[21]

That fall, Seeger took a job in Washington, D.C., assisting Alan Lomax, a friend of his father's, at the Archive of American Folk Song of the Library of Congress. Seeger's job was to help Lomax sift through commercial "race" and "hillbilly" music and select recordings that best represented American folk music, a project funded by the music division of the Pan American Union (later the Organization of American States), of whose music division his father, Charles Seeger, was head (1938–1953).[22] Lomax also encouraged Seeger's folk-singing vocation, and Seeger was soon appearing as a regular performer on Alan Lomax and Nicholas Ray's weekly Columbia Broadcasting show Back Where I Come From (1940–41) alongside Josh White, Burl Ives, Lead Belly, and Woody Guthrie (whom he had first met at Will Geer's Grapes of Wrath benefit concert for migrant workers on March 3, 1940). Back Where I Come From was unique in having a racially integrated cast.[23] The show was a success, but was not picked up by commercial sponsors for nationwide broadcasting because of its integrated cast. During the war, Seeger also performed on nationwide radio broadcasts by Norman Corwin.

From 1942 to 1945, Seeger served in the Army, as an Entertainment Specialist.[24]

In 1949, Seeger worked as the vocal instructor for the progressive City and Country School in Greenwich Village, New York.

Early activism

[edit]In 1936, at the age of 17, Pete Seeger joined the Young Communist League (YCL), then at the height of its influence. In 1942, he became a member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) itself,[26] but he left in 1949.[27]

In the spring of 1941, the twenty-one-year-old Seeger performed as a member of the Almanac Singers along with Millard Lampell, Cisco Houston, Woody Guthrie, Butch Hawes and Bess Lomax Hawes, and Lee Hays. Seeger and the Almanacs cut several albums of 78s on Keynote and other labels: Songs for John Doe (recorded in late February or March and released in May 1941), Talking Union, and an album each of sea shanties and pioneer songs. Written by Millard Lampell, Songs for John Doe was performed by Lampell, Seeger, and Hays, joined by Josh White and Sam Gary. It contained lines, such as "It wouldn't be much thrill to die for Du Pont in Brazil," that were sharply critical of Roosevelt's unprecedented peacetime draft (enacted in September 1940). This anti-war/anti-draft tone reflected the Communist Party line after the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which maintained that the war was "phony" and a mere pretext for big American corporations to get Hitler to attack Soviet Russia. Seeger has said he believed this line of argument at the time, as did many fellow members of the Young Communist League (YCL). Though nominally members of the Popular Front, which was allied with Roosevelt and more moderate liberals, the YCL's members still smarted from Roosevelt and Churchill's arms embargo on Loyalist Spain (which Roosevelt later called a mistake),[28] and the alliance frayed in the confusing welter of events.

A June 16, 1941, review in Time magazine, which, under its owner, Henry Luce, had become very interventionist, denounced the Almanacs' John Doe, accusing it of scrupulously echoing what it called "the mendacious Moscow tune" that "Franklin Roosevelt is leading an unwilling people into a J.P. Morgan war". Eleanor Roosevelt, a fan of folk music, reportedly found the album "in bad taste", though President Roosevelt, when the album was shown to him, merely observed, correctly, as it turned out, that few people would ever hear it. More alarmist was the reaction of eminent German-born Harvard Professor of Government Carl Joachim Friedrich, an adviser on domestic propaganda to the United States military. In a review in the June 1941 Atlantic Monthly, entitled "The Poison in Our System", he pronounced Songs for John Doe "strictly subversive and illegal", "whether Communist or Nazi financed", and "a matter for the attorney general", observing further that "mere" legal "suppression" would not be sufficient to counteract this type of populist poison,[29] the poison being folk music and the ease with which it could be spread.[30]

While the U.S. had not officially declared war on the Axis powers in the summer of 1941, the country was energetically producing arms and ammunition for its allies overseas. Despite the boom in manufacturing this concerted rearming effort brought, African Americans were barred from working in defense plants. Racial tensions rose as Black labor leaders (such as A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin) and their white allies began organizing protests and marches. To combat this social unrest, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 (the Fair Employment Act) on 25 June 1941. The order came three days after Hitler broke the non-aggression pact and invaded the Soviet Union, at which time the Communist Party quickly directed its members to get behind the draft and forbade participation in strikes for the duration of the war—angering some leftists. Copies of Songs for John Doe were removed from sale, and the remaining inventory destroyed, though a few copies may exist in the hands of private collectors.[31] The Almanac Singers' Talking Union album, on the other hand, was reissued as an LP by Folkways (FH 5285A) in 1955 and is still available. The following year, the Almanacs issued Dear Mr. President, an album in support of Roosevelt and the war effort. The title song, "Dear Mr. President", was a solo by Pete Seeger, and its lines expressed his lifelong credo:

Now, Mr. President,

We haven't always agreed in the past, I know,

But that ain't at all important now.

What is important is what we got to do,

We got to lick Mr. Hitler, and until we do,

Other things can wait.

Now, as I think of our great land ...

I know it ain't perfect, but it will be someday,

Just give us a little time.

This is the reason that I want to fight,

Not 'cause everything's perfect, or everything's right.

No, it's just the opposite: I'm fightin' because

I want a better America, and better laws,

And better homes, and jobs, and schools,

And no more Jim Crow, and no more rules like

"You can't ride on this train 'cause you're a Negro,"

"You can't live here 'cause you're a Jew,"

"You can't work here 'cause you're a union man."

So, Mr. President,

We got this one big job to do

That's lick Mr. Hitler and when we're through,

Let no one else ever take his place

To trample down the human race.

So what I want is you to give me a gun

So we can hurry up and get the job done.

Seeger's critics, however, continued to bring up the Almanacs' repudiated Songs for John Doe. In 1942, a year after the John Doe album's brief appearance (and disappearance), the FBI decided that the now-pro-war Almanacs were still endangering the war effort by subverting recruitment. According to the New York World Telegram (February 14, 1942), Carl Friedrich's 1941 article "The Poison in Our System" was printed up as a pamphlet and distributed by the Council for Democracy (an organization that Friedrich and Henry Luce's right-hand man, C. D. Jackson, Vice President of Time magazine, had founded "to combat all the Nazi, fascist, communist, pacifist" antiwar groups in the United States).[32]

Seeger served in the U.S. Army in the Pacific.[33] He was trained as an airplane mechanic, but was reassigned to entertain the American troops with music.[citation needed] Later, when people asked him what he did in the war, he always answered: "I strummed my banjo."[34] After returning from service, Seeger and others established People's Songs, conceived as a nationwide organization with branches on both coasts and designed to "create, promote and distribute songs of labor and the American People".[35] With Pete Seeger as its director, People's Songs worked for the 1948 presidential campaign of Roosevelt's former Secretary of Agriculture and Vice President, Henry A. Wallace, who ran as a third-party candidate on the Progressive Party ticket. Despite having attracted enormous crowds nationwide, however, Wallace did not win any electoral votes, and following the election, he was excoriated for accepting the help in his campaign of Communists and fellow travelers, such as Seeger and singer Paul Robeson.[36]

Spanish Civil War songs

[edit]Seeger had been a fervent supporter of the Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War. In 1943, with Tom Glazer and Bess and Baldwin Hawes, he recorded an album of 78s called Songs of the Lincoln Battalion on Moe Asch's Stinson label. This included such songs as "There's a Valley in Spain Called Jarama" and "Viva la Quince Brigada". In 1960, this collection was re-issued by Moe Asch as one side of a Folkways LP called Songs of the Lincoln and International Brigades. On the other side was a reissue of the legendary Six Songs for Democracy (originally recorded in Barcelona in 1938 while bombs were falling), performed by Ernst Busch and a chorus of members of the Thälmann Battalion, made up of volunteers from Germany. The songs were "Moorsoldaten" ("Peat Bog Soldiers", composed by political prisoners of German concentration camps); "Die Thaelmann-Kolonne", "Hans Beimler", "Das Lied von der Einheitsfront" ("Song of the United Front" by Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht), "Lied der Internationalen Brigaden" ("Song of the International Brigades"), and "Los cuatro generales" ("The Four Generals", known in English as "The Four Insurgent Generals").

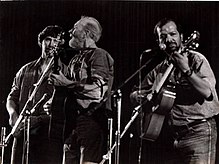

Group recordings

[edit]As a self-described "split tenor" (between a tenor and a countertenor),[37] Pete Seeger was a founding member of two highly influential folk groups: the Almanac Singers and the Weavers. The Almanac Singers, which Seeger co-founded in 1941 with Millard Lampell and Arkansas singer and activist Lee Hays, was a topical group, designed to function as a singing newspaper promoting the industrial unionization movement,[38] racial and religious inclusion, and other progressive causes. Its personnel included, at various times: Woody Guthrie, Bess Lomax Hawes, Sis Cunningham, Josh White, and Sam Gary. As a controversial Almanac singer, the 21-year-old Seeger performed under the stage name "Pete Bowers" to avoid compromising his father's government career.

In 1950, the Almanacs were reconstituted as the Weavers, named after the title of an 1892 play by Gerhart Hauptmann, about a workers' strike (which contained the lines "We'll stand it no more, come what may!"). They did benefits for strikers, at which they sang songs such as "Talking Union", about the struggles for unionisation of industrial workers such as miners and automobile workers.[39] Besides Pete Seeger (performing under his own name), members of the Weavers included charter Almanac member Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, and Fred Hellerman; later Frank Hamilton, Erik Darling, and Bernie Krause serially took Seeger's place. In the atmosphere of the 1950s red scare, the Weavers' repertoire had to be less overtly topical than that of the Almanacs had been, and its progressive message was couched in indirect language. The Weavers on occasion performed in tuxedos (unlike the Almanacs, who had dressed informally) and their managers refused to let them perform at political venues. The Weavers' string of major hits began with "On Top of Old Smoky" and an arrangement of Lead Belly's signature waltz, "Goodnight, Irene",[4] which topped the charts for 13 weeks in 1950[40] and was covered by many other pop singers. On the flip side of "Irene" was the Israeli song "Tzena, Tzena, Tzena".[4] Other Weavers hits included "Dusty Old Dust" ("So Long It's Been Good to Know You" by Woody Guthrie), "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine" (by Hays, Seeger, and Lead Belly), and the Zulu song by Solomon Linda, "Wimoweh" (about Shaka), among others.

The Weavers' performing career was abruptly derailed in 1953, at the peak of their popularity, when blacklisting prompted radio stations to refuse to play their records and all their bookings were canceled. They briefly returned to the stage, however, at a sold-out reunion at Carnegie Hall in 1955 and in a subsequent reunion tour, which produced a hit version of Merle Travis's "Sixteen Tons", as well as LPs of their concert performances. "Kumbaya", a Gullah black spiritual dating from slavery days, was also introduced to wide audiences by Pete Seeger and the Weavers (in 1959), becoming a staple of Boy and Girl Scout campfires.

In the late 1950s, the Kingston Trio was formed in direct imitation of (and homage to) the Weavers, covering much of the latter's repertoire, though with a more buttoned-down, uncontroversial, and mainstream collegiate persona. The Kingston Trio produced another phenomenal succession of Billboard chart hits and, in its turn, spawned a legion of imitators, laying the groundwork for the 1960s commercial folk revival.

In the documentary film Pete Seeger: The Power of Song (2007), Seeger states that he resigned from the Weavers when the three other band members agreed to perform a jingle for a cigarette commercial.

Banjo and 12-string guitar

[edit]

In 1948, Seeger wrote the first version of How to Play the Five-String Banjo, a book that many[who?] banjo players credit with starting them off on the instrument. He went on to invent the long-neck or Seeger banjo. This instrument is three frets longer than a typical banjo, is slightly longer than a bass guitar at 25 frets, and is tuned a minor third lower than the normal 5-string banjo. Hitherto strictly limited to the Appalachian region,[citation needed] the five-string banjo became known nationwide as the American folk instrument par excellence, largely thanks to Seeger's championing of and improvements to it. According to an unnamed musician quoted in David King Dunaway's biography, "by nesting a resonant chord between two precise notes, a melody note and a chiming note on the fifth string", Pete Seeger "gentrified" the more percussive traditional Appalachian "frailing" style, "with its vigorous hammering of the forearm and its percussive rapping of the fingernail on the banjo head".[41] Although what Dunaway's informant describes is the age-old droned frailing style, the implication is that Seeger made this more acceptable to mass audiences by omitting some of its percussive complexities, while presumably still preserving the characteristic driving rhythmic quality associated with the style.

Inspired by his mentor Woody Guthrie, whose guitar was labeled "This machine kills fascists", Seeger emblazoned his banjo head in 1952 with the slogan "This Machine Surrounds Hate and Forces It to Surrender", writing those words on every subsequent banjo he owned.[42]

From the late 1950s on, Seeger also accompanied himself on the 12-string guitar, an instrument of Mexican origin that had been associated with Lead Belly, who had styled himself "the King of the 12-String Guitar". Seeger's distinctive custom-made guitars had a triangular soundhole. He combined the long scale length (approximately 28") and capo-to-key techniques that he favored on the banjo with a variant of drop-D (DADGBE) tuning, tuned two whole steps down with very heavy strings, which he played with thumb and finger picks.[43]

Interest in steelpan

[edit]In 1956, Seeger and his wife, Toshi, traveled to Port of Spain, Trinidad, to seek out information on the steelpan, sometimes called a steel drum, or "ping-pong". The two searched out a local panyard director, Isaiah, and proceeded to film the construction, tuning and playing of the then-new national instrument of Trinidad and Tobago. He was attempting to include the unique flavor of the steelpan in American folk music.

McCarthy era

[edit]In the 1950s, and indeed consistently throughout his life, Seeger continued his support of civil and labor rights, racial equality, international understanding, and anti-militarism (all of which had characterized the Wallace campaign), and he continued to believe that songs could help people achieve these goals. However, with the ever-growing revelations of Joseph Stalin's atrocities and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, he became increasingly disillusioned with Soviet Socialism. He left the CPUSA in 1949, but remained friends with some who did not leave it, although he argued with them about it.[44][45]

On August 18, 1955, Seeger was subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Alone among the many witnesses after the 1950 conviction and imprisonment of the Hollywood Ten for contempt of Congress, Seeger refused to plead the Fifth Amendment (which would have asserted that his testimony might be self-incriminating) and instead, as the Hollywood Ten had done, refused to name personal and political associations on the grounds that this would violate his First Amendment rights: "I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election, or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this."[46][47] Seeger's refusal to answer questions that he believed violated his fundamental constitutional rights led to a March 26, 1957, indictment for contempt of Congress; for some years, he had to keep the federal government apprised of where he was going any time he left the Southern District of New York. He was convicted in a jury trial of contempt of Congress in March 1961, and sentenced to ten one-year terms in jail (to be served simultaneously), but in May 1962, an appeals court ruled the indictment to be flawed and overturned his conviction.[48][49]

In 1960, the San Diego school board told him that he could not play a scheduled concert at a high school unless he signed an oath pledging that the concert would not be used to promote a communist agenda or an overthrow of the government. Seeger refused, and the American Civil Liberties Union obtained an injunction against the school district, allowing the concert to go on as scheduled. Almost 50 years later, in February 2009, the San Diego School District officially extended an apology to Seeger for the actions of its predecessors.[50]

Folk music revival

[edit]To earn money during the blacklist period of the late 1950s and early 1960s, Seeger worked gigs as a music teacher in schools and summer camps, and traveled the college campus circuit. He also recorded as many as five albums a year for Moe Asch's Folkways Records label. As the nuclear disarmament movement picked up steam in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Seeger's anti-war songs, such as "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?" (co-written with Joe Hickerson), "Turn! Turn! Turn!"[51] adapted from the Book of Ecclesiastes, and "The Bells of Rhymney" by the Welsh poet Idris Davies[52] (1957), gained wide currency. Seeger was the first person to make a studio recording of "Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream" in 1956. Seeger also was closely associated with the Civil Rights Movement and in 1963 helped organize a landmark Carnegie Hall concert, featuring the youthful Freedom Singers, as a benefit for the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. This event, and Martin Luther King Jr.'s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August of that same year, brought the civil rights anthem "We Shall Overcome" to wide audiences. He sang it on the 50-mile walk from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, along with 1,000 other marchers.[53] By this time, Seeger was a senior figure in the 1960s folk revival centered in Greenwich Village, as a longtime columnist in Sing Out!, the successor to the People's Songs Bulletin, and as a founder of the topical Broadside magazine. To describe the new crop of politically committed folk singers, he coined the phrase "Woody's children", alluding to his associate and traveling companion, Woody Guthrie, who by this time had become a legendary figure. This urban folk-revival movement, a continuation of the activist tradition of the 1930s and 1940s and of People's Songs, used adaptations of traditional tunes and lyrics to effect social change, a practice that goes back to the Industrial Workers of the World or Wobblies' Little Red Song Book, compiled by Swedish-born union organizer Joe Hill (1879–1915) (the Little Red Song Book had been a favorite of Woody Guthrie, who was known to carry it around).[54]

Seeger toured Australia in 1963. His single "Little Boxes", written by Malvina Reynolds, was number one in the nation's Top 40. That tour sparked a folk boom throughout the country at a time when popular music tastes, post–Kennedy assassination, competed between folk, the surfing craze, and the British rock boom that gave the world the Beatles and The Rolling Stones, among others. Folk clubs sprang up all over the nation; folk performers were accepted in established venues; Australian performers singing Australian folk songs—many of their own composing—emerged in concerts and festivals, on television, and on recordings; and overseas performers were encouraged to tour Australia.[citation needed]

The long television blacklist of Seeger began to end in the mid-1960s when he hosted a regionally broadcast educational folk-music television show, Rainbow Quest. Among his guests were Johnny Cash, June Carter, Reverend Gary Davis, Mississippi John Hurt, Doc Watson, the Stanley Brothers, Elizabeth Cotten, Patrick Sky, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Tom Paxton, Judy Collins, Hedy West, Donovan, The Clancy Brothers, Richard Fariña and Mimi Fariña, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Mamou Cajun Band, Bernice Johnson Reagon, the Beers Family, Roscoe Holcomb, Malvina Reynolds, Sonia Malkine, and Shawn Phillips. Thirty-nine[44] hour-long programs were recorded at WNJU's Newark studios in 1965 and 1966, produced by Seeger and his wife Toshi, with Sholom Rubinstein. The Smothers Brothers ended Seeger's national blacklisting by broadcasting him singing "Waist Deep in the Big Muddy" on their CBS variety show on February 25, 1968, after his similar performance in September 1967 was censored by CBS.[55]

In November 1976, Seeger wrote and recorded the anti-death penalty song "Delbert Tibbs", about the death-row inmate Delbert Tibbs, who was later exonerated. Seeger wrote the music and selected the words from poems written by Tibbs.[56]

Seeger also supported the Jewish Camping Movement. He came to Surprise Lake Camp in Cold Spring, New York, over the summer many times.[57] He sang and inspired countless campers.[58]

Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan

[edit]Pete Seeger was one of the earliest backers of Bob Dylan; he was responsible for urging A&R man John Hammond to produce Dylan's first LP on Columbia, and for inviting him to perform at the Newport Folk Festival, of which Seeger was a board member.[59] There was a widely repeated story that Seeger was so upset over the extremely loud amplified sound that Dylan, backed by members of the Butterfield Blues Band, brought into the 1965 Newport Folk Festival that he threatened to disconnect the equipment. There are multiple versions of what went on, some fanciful. What is certain is that tensions had been running high between Dylan's manager Albert Grossman and Festival board members (who besides Seeger also included Theodore Bikel, Bruce Jackson, Alan Lomax, festival MC Peter Yarrow, and George Wein) over the scheduling of performers and other matters. Two days earlier, there had been a scuffle and a brief exchange of blows between Grossman and Alan Lomax, and the board, in an emergency session, had voted to ban Grossman from the grounds, but had backed off when George Wein pointed out that Grossman also managed highly popular draws Odetta and Peter, Paul and Mary.[60] Seeger has been portrayed as a folk "purist" who was one of the main opponents to Dylan's "going electric",[61] but when asked in 2001 about how he recalled his "objections" to the electric style, he said:

I couldn't understand the words. I wanted to hear the words. It was a great song, "Maggie's Farm," and the sound was distorted. I ran over to the guy at the controls and shouted, "Fix the sound so you can hear the words." He hollered back, "This is the way they want it." I said "Damn it, if I had an axe, I'd cut the cable right now." But I was at fault. I was the MC, and I could have said to the part of the crowd that booed Bob, "you didn't boo Howlin' Wolf yesterday. He was electric!" Though I still prefer to hear Dylan acoustic, some of his electric songs are absolutely great. Electric music is the vernacular of the second half of the twentieth century, to use my father's old term.[62]

Vietnam War era and beyond

[edit]

A longstanding opponent of the arms race and of the Vietnam War, Seeger satirically attacked then-President Lyndon Johnson with his 1966 recording, on the album Dangerous Songs!?, of Len Chandler's children's song "Beans in My Ears". Beyond Chandler's lyrics, Seeger said that "Mrs. Jay's little son Alby" had "beans in his ears", which, as the lyrics imply,[63] ensures that a person does not hear what is said to them. To those opposed to continuing the Vietnam War, the phrase implied that "Alby Jay", a loose pronunciation of Johnson's nickname "LBJ", did not listen to anti-war protests as he too had "beans in his ears".

During 1966, Seeger and Malvina Reynolds took part in environmental activism. The album God Bless the Grass was released in January of that year and became the first album in history wholly dedicated to songs about environmental issues. Their politics were informed by the same ideologies of nationalism, populism, and criticism of big business.[64]

Seeger attracted wider attention starting in 1967 with his song "Waist Deep in the Big Muddy", about a captain—referred to in the lyrics as "the big fool"—who drowned while leading a platoon on maneuvers in Louisiana during World War II. With its lyrics about a platoon being led into danger by an ignorant captain, the song's anti-war message was obvious—the line "the big fool said to push on" is repeated several times.[65] In the face of arguments with the management of CBS about whether the song's political weight was in keeping with the usually light-hearted entertainment of the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, the final lines were "Every time I read the paper/those old feelings come on/We are waist deep in the Big Muddy and the big fool says to push on." The lyrics could be interpreted as an allegory of Johnson as the "big fool" and the Vietnam War as the foreseeable danger. Although the performance was cut from the September 1967 show,[66] after wide publicity,[67] it was broadcast when Seeger appeared again on the Smothers' Brothers show on February 25, 1968.[68]

At the November 15, 1969, Vietnam Moratorium March on Washington, DC, Seeger led 500,000 protesters in singing John Lennon's song "Give Peace a Chance" as they rallied across from the White House. Seeger's voice carried over the crowd, interspersing phrases like "Are you listening, Nixon?" between the choruses of protesters singing, "All we are saying ... is give peace a chance."[69]

In the documentary film The Power of Song, Seeger mentions that he and his family visited the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1972.[70] Phạm Tuyên composed "Let me hear your guitar, my U.S. friend" ("Gảy đàn lên hỡi người bạn Mỹ") as a tribute to Seeger's support for the DRV. When Seeger and his wife arrived at the airport, Phạm Tuyên greeted them and they sang the song together.[71]

Being a supporter of progressive labor unions, Seeger had supported Ed Sadlowski in his bid for the presidency of the United Steelworkers of America. In 1977, Seeger appeared at a fundraiser in Homestead, Pennsylvania. In 1978, Seeger joined American folk, blues, and jazz singer Barbara Dane at a rally in New York for striking coal miners.[72] He also headlined a benefit concert—with bluegrass artist Hazel Dickens—for the striking coal miners of Stearns, Kentucky, at the Lisner Auditorium in Washington, D.C., on June 8, 1979.[73]

In 1980, Pete Seeger performed in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The performance was later released by Smithsonian Folkways as the album Singalong Sanders Theater, 1980.[74]

Hudson River sloop Clearwater

[edit]

In 1966, Seeger and his wife Toshi founded the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, a nonprofit organization based in Poughkeepsie, New York, that sought to protect the Hudson River and surrounding wetlands and waterways through advocacy and public education. It constructed a floating ambassador for this environmental mission, the sloop Clearwater, and began an annual music and environmental festival, today known as the Great Hudson River Revival.[75]

Reflection on support for Soviet communism

[edit]In 1982, Seeger performed at a benefit concert for the 1982 demonstrations in Poland against the Polish government. His biographer David Dunaway considers this the first public manifestation of Seeger's decades-long personal dislike of socialism in its Soviet form.[76] In the late 1980s, Seeger also expressed disapproval of violent revolutions, remarking to an interviewer that he was really in favor of incremental change and that "the most lasting revolutions are those that take place over a period of time".[76] In his autobiography Where Have All the Flowers Gone (1993, 1997, reissued in 2009), Seeger wrote, "Should I apologize for all this? I think so." He went on to put his thinking in context:

How could Hitler have been stopped? Litvinov, the Soviet delegate to the League of Nations in '36, proposed a worldwide quarantine but got no takers. For more on those times check out pacifist Dave Dellinger's book, From Yale to Jail ... [77] At any rate, today I'll apologize for a number of things, such as thinking that Stalin was merely a "hard driver" and not a "supremely cruel misleader". I guess anyone who calls himself a Christian should be prepared to apologize for the Inquisition, the burning of heretics by Protestants, the slaughter of Jews and Muslims by Crusaders. White people in the U.S.A. ought to apologize for stealing land from Native Americans and enslaving blacks. Europeans could apologize for worldwide conquests, Mongolians for Genghis Khan. And supporters of Roosevelt could apologize for his support of Somoza, of Southern White Democrats, of Franco Spain, for putting Japanese Americans in concentration camps. Who should my granddaughter Moraya apologize to? She's part African, part European, part Chinese, part Japanese, part Native American. Let's look ahead.[78][79]

In a 1995 interview, however, he insisted that "I still call myself a communist, because communism is no more what Russia made of it than Christianity is what the churches make of it".[80] In later years, as the aging Seeger began to garner awards and recognition for his lifelong activism, he also found himself criticized once again for his opinions and associations of the 1930s and 1940s. In 2006, David Boaz—Voice of America and NPR commentator and president of the libertarian Cato Institute—wrote an opinion piece in The Guardian, entitled "Stalin's Songbird", in which he excoriated The New Yorker and The New York Times for lauding Seeger. He characterized Seeger as "someone with a longtime habit of following the party line" who had only "eventually" parted ways with the CPUSA. In support of this view, he quoted lines from the Almanac Singers' May 1941 Songs for John Doe, contrasting them darkly with lines supporting the war from Dear Mr. President, issued in 1942, after the United States and the Soviet Union had entered the war.[81][82]

In 2007, in response to criticism from historian Ron Radosh, a former Trotskyist who now writes for the conservative National Review, Seeger wrote a song condemning Stalin, "Big Joe Blues":[83]

I'm singing about old Joe, cruel Joe.

He ruled with an iron hand.

He put an end to the dreams

Of so many in every land.

He had a chance to make

A brand new start for the human race.

Instead he set it back

Right in the same nasty place.

I got the Big Joe Blues.

Keep your mouth shut or you will die fast.

I got the Big Joe Blues.

Do this job, no questions asked.

I got the Big Joe Blues.[84]

The song was accompanied by a letter to Radosh, in which Seeger stated, "I think you're right, I should have asked to see the gulags when I was in U.S.S.R. [in 1965]."[79]

Later work

[edit]

Seeger appears in the 1997 documentary film An Act of Conscience, which was filmed between 1988 and 1995. In the film, Seeger joins a group of demonstrators protesting in support of war tax resisters Randy Kehler and Betsy Corner, whose home was seized by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) after the couple openly refused to pay their federal income taxes as a protest against war and military spending.[85]

In 2003, Pete Seeger was a participant in an anti-Iraq war protest.[86]

On March 16, 2007, Pete Seeger, his sister Peggy, his brothers Mike and John, his wife Toshi, and other family members spoke and performed at a symposium and concert sponsored by the American Folklife Center in honor of the Seeger family, held at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.,[87] where Pete Seeger had been employed by the Archive of American Folk Song 67 years earlier.

In September 2008, Appleseed Recordings released At 89, Seeger's first studio album in 12 years. On September 29, 2008, the 89-year-old singer-activist, once banned from commercial TV, made a rare national TV appearance on the Late Show with David Letterman, singing "Take It From Dr. King".

On January 18, 2009, Seeger and his grandson Tao Rodríguez-Seeger joined Bruce Springsteen and the crowd in singing the Woody Guthrie song "This Land Is Your Land" in the finale of Barack Obama's inaugural concert in Washington, D.C.[88][89] The performance was noteworthy for the inclusion of two verses not often included in the song, one about a "private property" sign the narrator cheerfully ignores, and the other making a passing reference to a Depression-era relief office. The former's final line, however, "This land was made for you and me", is modified to "That side was made for you and me".[88][90]

Over the years, he lent his fame to support numerous environmental organizations, including South Jersey's Bayshore Center, the home of New Jersey's tall ship, the oyster schooner A.J. Meerwald. Seeger's benefit concerts helped raise funds for groups so they could continue to educate and spread environmental awareness.[91] On May 3, 2009, at the Clearwater Concert, dozens of musicians gathered in New York at Madison Square Garden to celebrate Seeger's 90th birthday (which was later televised on PBS during the summer),[92] ranging from Dave Matthews, John Mellencamp, Billy Bragg, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Morello, Eric Weissberg, Ani DiFranco and Roger McGuinn to Joan Baez, Richie Havens, Joanne Shenandoah, R. Carlos Nakai, Bill Miller, Joseph Fire Crow, Margo Thunderbird, Tom Paxton, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, and Arlo Guthrie. Cuban singer-songwriter Silvio Rodríguez was also invited to appear, but his visa was not approved in time by the United States government. Consistent with Seeger's longtime advocacy for environmental concerns, the proceeds from the event benefited the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater,[93] a non-profit organization founded by Seeger in 1966, to defend and restore the Hudson River. Seeger's 90th birthday was also celebrated at The College of Staten Island on May 4.[94][95][96] On September 19, 2009, Seeger made his first appearance at the 52nd Monterey Jazz Festival, which was particularly notable because the festival does not normally feature folk artists.

In 2010, still active at the age of 91, Seeger co-wrote and performed the song "God's Counting on Me, God's Counting on You" with Lorre Wyatt, commenting on the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.[97] A performance of the song by Seeger, Wyatt, and friends was recorded and filmed aboard the sloop Clearwater in August for a single and video produced by Richard Barone and Matthew Billy, released on election day, November 6, 2012.[98]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

On October 21, 2011, at age 92, Pete Seeger was part of a solidarity march with Occupy Wall Street to Columbus Circle in New York City.[100] The march began with Seeger and fellow musicians exiting Symphony Space (95th and Broadway), where they had performed as part of a benefit for Seeger's Clearwater organization. Thousands of people crowded Pete Seeger by the time they reached Columbus Circle, where he performed with his grandson, Tao Rodríguez-Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, David Amram, and other celebrated musicians.[101] The event, promoted under the name OccupyTheCircle, was livestreamed, and was dubbed by some "the Pete Seeger March".

In January 2012, Seeger joined the Rivertown Kids in paying tribute to his friend Bob Dylan, performing Dylan's "Forever Young" on the Amnesty International album Chimes of Freedom.[102] This song, Seeger's last single, marked Seeger's only music video, which went viral in the wake of his death two years later.[103]

On December 14, 2012, Seeger performed, along with Harry Belafonte, Jackson Browne, Common, and others, at a concert to bring awareness to the 37-year-long ordeal of Native American activist Leonard Peltier. The concert was held at the Beacon Theatre in New York City.[104]

On April 9, 2013, Hachette Audio Books issued an audiobook entitled Pete Seeger: The Storm King; Stories, Narratives, Poems. This two-CD spoken-word work was conceived of and produced by noted percussionist Jeff Haynes and presents Pete Seeger telling the stories of his life against a background of music performed by more than 40 musicians of varied genres.[105] The launch of the audiobook was held at the Dia:Beacon on April 11, 2013, to an enthusiastic audience of around two hundred people, and featured many of the musicians from the project (among them Samite, Dar Williams, Dave Eggar, and Richie Stearns of the Horse Flies and Natalie Merchant) performing live under the direction of producer and percussionist Haynes.[106] April 15, 2013, Sirius XM Book Radio presented the Dia:Beacon concert as a special episode of Cover to Cover Live with Maggie Linton and Kim Alexander, entitled "Pete Seeger: The Storm King and Friends".[107]

On August 9, 2013, one month widowed, Seeger was in New York City for the 400-year commemoration of the Two Row Wampum Treaty between the Iroquois and the Dutch. On an interview he gave that day to Democracy Now!, Seeger sang "I Come and Stand at Every Door", as it was also the 68th anniversary of the bombing of Nagasaki.[108][109]

On September 21, 2013, Pete Seeger performed at Farm Aid at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center in Saratoga Springs, New York. Joined by Wille Nelson, Neil Young, John Mellencamp, and Dave Matthews, he sang "This Land Is Your Land",[110] and included a verse he said he had written specifically for the Farm Aid concert.

Personal life

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2023) |

Seeger married Toshi Aline Ohta in 1943, whom he credited with being the support that helped make the rest of his life possible. The couple remained married until Toshi's death in July 2013.[111] Their first child, Peter Ōta Seeger, was born in 1944 and died at six months, while Pete was deployed overseas. Pete never saw him.[112] They went on to have three more children: Daniel (an accomplished photographer and filmmaker), Mika (a potter and muralist), and Tinya (a potter), as well as grandchildren Tao Rodríguez-Seeger (a musician), Cassie (an artist), Kitama Cahill-Jackson (a psychotherapist), Moraya (a marriage and family therapist married to the NFL player Chris DeGeare), Penny, and Isabelle, and great-grandchildren Dio and Gabel. Tao, a folk musician in his own right, sings and plays guitar, banjo, and harmonica with the Mammals. Kitama Jackson is a documentary filmmaker who was associate producer of the 2007 PBS documentary Pete Seeger: The Power of Song.

When asked by Beliefnet about his religious or spiritual beliefs, and his definition of God, Seeger replied:

Nobody knows for sure. But people undoubtedly get feelings which are not explainable and they feel they're talking to God or they're talking to their parents who are long dead. I feel most spiritual when I'm out in the woods. I feel part of nature. Or looking up at the stars. [I used to say] I was an atheist. Now I say, it's all according to your definition of God. According to my definition of God, I'm not an atheist. Because I think God is everything. Whenever I open my eyes I'm looking at God. Whenever I'm listening to something I'm listening to God. I've had preachers of the gospel, Presbyterians and Methodists, saying, "Pete, I feel that you are a very spiritual person". And maybe I am. I feel strongly that I'm trying to raise people's spirits to get together. ... I tell people I don't think God is an old white man with a long white beard and no navel; nor do I think God is an old black woman with white hair and no navel. But I think God is literally everything, because I don't believe that something can come out of nothing. And so there's always been something. Always is a long time.

He was a member of a Unitarian Universalist Church in New York.[114]

Seeger lived in Beacon, New York. He and Toshi purchased their land in 1949 and lived there first in a trailer, then in a log cabin they built themselves. He remained engaged politically and maintained an active lifestyle in the Hudson Valley region of New York throughout his life. For years during the Iraq War, Seeger maintained a weekly protest vigil alongside Route 9 in Wappingers Falls, near his home. He told a New York Times reporter that "working for peace was like adding sand to a basket on one side of a large scale, trying to tip it one way despite enormous weight on the opposite side." He went on to say, "Some of us try to add more sand by teaspoons ... It's leaking out as fast as it goes in and they're all laughing at us. But we're still getting people with teaspoons. I get letters from people saying, 'I'm still on the teaspoon brigade.'"[115]

Toshi died in Beacon on July 9, 2013, at the age of 91,[111][116] and Pete died at New York–Presbyterian Hospital in New York City on January 27, 2014, at the age of 94.[117]

Legacy

[edit]Response and reaction to Seeger's death quickly poured in. President Barack Obama noted that Seeger had been called "America's tuning fork"[118] and that he believed in "the power of song" to bring social change, "Over the years, Pete used his voice and his hammer to strike blows for workers' rights and civil rights; world peace and environmental conservation, and he always invited us to sing along. For reminding us where we come from and showing us where we need to go, we will always be grateful to Pete Seeger."[119] Folksinger and fellow activist Billy Bragg wrote that "Pete believed that music could make a difference. Not change the world, he never claimed that – he once said that if music could change the world he'd only be making music – but he believed that while music didn't have agency, it did have the power to make a difference."[120] Bruce Springsteen said of Seeger's death, "I lost a great friend and a great hero last night, Pete Seeger," before performing "We Shall Overcome" while on tour in South Africa.[121]

Tributes

[edit]| External audio | |

|---|---|

- A proposal was made in 2009 to name the Walkway Over the Hudson in his honor.[122]

- A posthumous suggestion that Seeger's name be applied to the replacement Tappan Zee Bridge being built over the Hudson River was made by a local town supervisor.[75][123] Seeger's boat, the sloop Clearwater, is based at Beacon, New York, just upriver from the bridge and frequently sails down to Manhattan to continuing spreading Seeger's message and music.[124]

- Oakwood Friends School, located in Poughkeepsie New York, not far from Seeger's home, performed "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?" at one of their worship meetings. The collaboration was with three teachers (playing guitar and vocals) as well as a student harmonica player and a student vocalist.

- A free five-day memorial called Seeger Fest took place on July 17–21, 2014, featuring Judy Collins, Peter Yarrow, Harry Belafonte, Anti-Flag, Michael Glabicki of Rusted Root, Steve Earle, Holly Near, Fred Hellerman, Guy Davis, DJ Logic, Paul Winter Consort, Dar Williams, DJ Kool Herc, The Rappers Delight Experience, Tiokasin Ghosthorse, David amram, Mike + Ruthy, Tom Chapin, James Maddock, The Chapin Sisters, Rebel Diaz, Sarah Lee Guthrie & Johnny Irion, Elizabeth Mitchell, Emma's Revolution, Toni Blackman, Kim & Reggie Harris, Magpie, Abrazos Orchestra, Nyraine, George Wein, The Vanaver Caravan, White Tiger Society, Lorre Wyatt, AKIR, Adira & Alana Amram, Aurora Barnes, The Owens Brothers, The Tony Lee Thomas Band, Jay Ungar & Molly Mason, New York City Labor Chorus, Roland Moussa, Roots Revelators, Kristen Graves, Bob Reid, Hudson River Sloop Singers, Walkabout Clearwater Chorus, Betty & The baby Boomers, Work O' The Weavers, Jacob Bernz * Sarah Armour, and Amanda Palmer.[125]

- In 2006, thirteen folk music songs made popular by Pete Seeger were reinterpreted by Bruce Springsteen on his fourteenth studio album, We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions.

- In 2014, Wepecket Island Records recorded a Pete Seeger tribute album called For Pete's Sake.

- In 2020, Kronos Quartet released Long Time Passing, an album of all new arrangements of Pete Seeger's music commissioned by the FreshGrass Foundation and released on Smithsonian Folkways.

- On July 21, 2022, the United States Postal Service issued a Pete Seeger "Forever" stamp. The stamp is based on a photograph of Seeger playing a long neck banjo, taken by Seeger's son Daniel some time in the early 1960s. It's a commemorative in the Music Icons series, with a print quantity of 22,000,000.[126]

Awards

[edit]Seeger received many awards and recognitions throughout his career, including:

- Induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame (1972)[127]

- The Eugene V. Debs Award (1979)

- The Letelier-Moffitt Human Rights Award (1986)

- The Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (1993)[128]

- The National Medal of Arts from the National Endowment for the Arts (1994)

- Kennedy Center Honor (1994)

- The Harvard Arts Medal (1996)

- The James Smithson Bicentennial Medal (1996)[129]

- Induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1996)

- Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Album of 1996 for his record Pete (1997)

- The Felix Varela Medal, Cuba's highest honor for "his humanistic and artistic work in defense of the environment and against racism" (1999)

- The Schneider Family Book Award for his children's picture book The Deaf Musicians. (2007)

- The Mid-Hudson Civic Center Hall of Fame (2008)- Seeger and Arlo Guthrie performed the first public concert at the Poughkeepsie, New York not-for-profit family entertainment venue, close to Seeger's home, in 1976. Grandson Tao Rodríguez-Seeger accepted the Hall of Fame plaque on behalf of his grandfather.

- Grammy Award for Best Traditional Folk Album of 2008 for his record At 89 (2009)

- The Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Award[130] for his commitment to peace and social justice as a musician, songwriter, activist, and environmentalist that spans over sixty years. (2008)

- The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize (2009)

- Grammy Award for Best Musical Album for Children of 2010 for his record album Tomorrow's Children with the Rivertown Kids and Friends (2011)

- George Peabody Medal (2013)

- Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album of 2013 nomination for Pete Seeger: The Storm King; Stories, Narratives, Poems (2014)[131][132]

- Woody Guthrie Prize (2014) (inaugural recipient)[133]

Selected discography

[edit]- American Folk Songs for Children (1953)

- Birds, Beasts, Bugs, and Little Fishes (1955)

- American Industrial Ballads (1956)

- American Favorite Ballads, Vol. 2 (1958)

- Gazette, Vol. 1 (1958)

- Sleep-Time: Songs & Stories (1958)

- God Bless the Grass (1966)

- Dangerous Songs!? (1966)

- Rainbow Race (1973)

- American Folk Songs for Children (1990)

- At 89 (2008)[134][135]

See also

[edit]- List of banjo players

- List of peace activists

- Tom Winslow – Clearwater singer and songwriter

- Union Boys

Notes

[edit]- ^ Clapp, E.P. (September 14, 2013). "Honor Pete Seeger". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ David King Dunaway, How Can I Keep From Singing (New York: [Random House, 1981, 1990], revised edition, Villard Books, 2008), p. 17.

- ^ See Ann M. Pescatello, Charles Seeger: A Life in American Music (University of Pittsburgh, 1992), pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c Pete Seeger interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- ^ Dunaway (2008), p. 20.

- ^ According to Dunaway, the British-born president of the university "all but fired" Charles Seeger (How Can I Keep From Singing, p. 26).

- ^ Ann Pescatello, Charles Seeger: A Life In Music, 83–85.

- ^ Dunaway, How Can I Keep From Singing, p. 32. Frank Damrosch, siding with Constance, fired Charles from Juilliard, see Judith Tick, Ruth Crawford Seeger: a Composer's Search for American Music (Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 224–25.

- ^ Dunaway, How Can I Keep From Singing, pp. 22, 24.

- ^ Winkler (2009), p. 4.

- ^ See Judith Tick, Ruth Crawford Seeger: a Composer's Search for American Music (1997). Archived May 11, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "David Lewis, Ruth Crawford Seeger Biography in 600 Words on website of her daughter, Peggy Seeger". Peggyseeger.com. February 14, 2005. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ "John Seeger Dies at 95". WordPress.com. January 18, 2010. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ Wilkinson, "The Protest Singer" (2006) p. 50 and Dunaway, How Can I Keep From Singing, p. 32.

- ^ Alec Wilkinson, The Protest Singer: An Intimate Portrait of Pete Seeger (New York: Knopf, 2009), p. 43.

- ^ Dunaway, How Can I Keep From Singing, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Judith Tick, Ruth Crawford Seeger, p. 239.

- ^ Judith Tick, Ruth Crawford Seeger, p. 235. According to John Szwed, Jackson Pollock, later famous for his "drip" paintings, played harmonica, having smashed his violin in frustration, see: Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World (Viking, 2010), p. 88.

- ^ According to Wilkinson, "The Protest Singer" (2006), p. 51, after failing one of his winter exams and losing his scholarship.

- ^ Dunaway, How Can I Keep From Singing, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Emery, Lawrence, "Interesting Summer: Young Puppeteers in Unique Tour of Rural Areas", quoted on Pete Seeger website

- ^ The resultant 22-page mimeographed "List of American Folk Music on Commercial Recordings", issued in 1940 and mailed by Lomax out to academic folklore scholars, became the basis of Harry Smith's celebrated Anthology of American Folk Music on Folkways Records. Seeger also did similar work for Lomax at Decca in the late 1940s.

- ^ Folk Songs in the White House, Time, March 3, 1941

- ^ "Seeger, Pete, Cpl". army.togetherweserved.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ From the Washington Post, February 12, 1944: "The Labor Canteen, sponsored by the United Federal Workers of America, CIO, will be opened at 8 p.m. tomorrow at 1212 18th st. nw. Mrs. Roosevelt is expected to attend at 8:30 p.m."

- ^ Reineke, Hank (2023). Rising Son: The Life and Music of Arlo Guthrie. American Popular Music. Vol. 10. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780806193588.

- ^ He later commented "Innocently I became a member of the Communist Party, and when they said fight for peace, I did, and when they said fight Hitler, I did. I got out in '49, though. ... I should have left much earlier. It was stupid of me not to. My father had got out in '38, when he read the testimony of the trials in Moscow, and he could tell they were forced confessions. We never talked about it, though, and I didn't examine closely enough what was going on. ... I thought Stalin was the brave secretary Stalin, and had no idea how cruel a leader he was." Wilkinson, "The Protest Singer" (2006), p. 52; see also The Protest Singer: An Intimate Portrait (2009), p. 116.

- ^ Dallek, Robert (1995). "'Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945"'. Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780199826667. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ "The Poison in Our System" (excerpt from the Atlantic Monthly) by Carl Joachim Friedrich Archived June 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Note: Dunaway misses the significance of military propagandist Carl Joachim Friedrich, when he mistakenly refers to him as "Karl Frederick," an error other writers who relied on Dunaway repeated.

- ^ Friedrich's review concluded: "The three records sell for one dollar and you are asked to 'play them in your home, play them in your union hall, take them back to your people.' Probably some of these songs fall under the criminal provisions of the Selective Service Act, and to that extent it is a matter for the Attorney-General. But you never can handle situations of this kind democratically by mere suppression. Unless civic groups and individuals will make a determined effort to counteract such appeals by equally effective methods, democratic morale will decline." Upon United States entry into the war in 1942, Friedrich became chairman of the Executive Committee of the Council for Democracy, charged with combatting isolationism, and had his article on the Almanacs Archived June 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine reprinted as one of several pamphlets which he sent to radio network executives.

- ^ Although the Almanacs were accused – both at the time and in subsequent histories – of reversing their attitudes in response to the Communist Party's new party line, "Seeger has pointed out that virtually all progressives reversed course and supported the war. He insists that no one, Communist Party or otherwise, told the Almanacs to change their songs. (Seeger interview with [Richard A.] Reuss 4/9/68)" quoted in William G. Roy, "Who Shall Not Be Moved? Folk Music, Community and Race in the American The Communist Party and the Highlander School," ff p. 16. Archived March 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Blanche Wiessen Cook, Eisenhower Declassified (Doubleday, 1981), page 122. "The Council was a limited affair," Cook writes, "... that served mostly to highlight Jackson's talents as a propagandist."

- ^ Billboard Magazine – Article on Pete Seegar 12/19/2015| https://www.billboard.com/music/music-news/military-fbi-woody-guthrie-pete-seeger-wartime-world-war-two-6813894/ Archived September 22, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Minzesheimer, Bob (January 28, 2014). "Pete Seeger taught America to sing, and think". USA TODAY. Retrieved October 27, 2024.

- ^ People's Songs Inc. People's Songs Newsletter No 1. February 1946. Old Town School of Folk Music Resource center collection.

- ^ American Masters: "Pete Seeger: The Power of Song – KQED Broadcast 2-27-08.

- ^ Wilkinson, "The Protest Singer" (2006), p. 47.

- ^ See Wikipedia entry on the CIO.

- ^ Ingram, David. "The Jukebox in the Garden: Ecocriticism and American Popular Music Since 1960." Humanities Source. 2010 Vol. 7. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ Alec Wilkinson, "The Protest Singer: Pete Seeger and American folk music," in The New Yorker (April 17, 2006), pp. 44–53.

- ^ Dunaway, How Can I Keep from Singing, p. 100.

- ^ "Pete Seeger's banjo". Flickr. March 18, 2006. Archived from the original on March 22, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ "Acoustic Guitar Central". Acousticguitar.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ a b "Pete Seeger: The Power of Song" Archived August 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine – PBS American Masters, February 27, 2008

- ^ Pete Seeger Interview PBS American Masters.

- ^ Pete Seeger to the House Un-American Activities Committee, August 18, 1955. Quoted, along with some other exchanges from that hearing, in Wilkinson, "The Protest Singer" (2006), p. 53.

- ^ United States. Congress. House. Committee on Un-American Activities (August 17–18, 1955). Investigation of Communist Activities, New York Area— Part VII (Entertainment). Hearings Before the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-Fourth Congress, First Session, August 17 And 18, 1955. Vol. pt. 7. Washington, U.S. Govt. Print. Off. pp. Testimony of Peter Seeger, p. 2447–2459.

- ^ United States v. Seeger Archived August 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, 303 F. 2d 478 (2d Cir. 1962).

- ^ Wilkinson, "The Protest Singer" (2006), p. 53.

- ^ Dillon, Raquel Maria. "School board offers apology to singer Pete Seeger". Sign on San Diego. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ Pete Seeger interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- ^ "BBC News – South East Wales". BBC. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ Whitehead, John. "Pete Seeger: Changing the World One Song at a Time." Waxahachie Daily Light. May 30, 2013. Rutherford Institute. Accessed on October 14, 2014.

- ^ Briley, Ronald (2006). ""Woody Sez": Woody Guthrie, the "People's Daily World," and Indigenous Radicalism". California History. 84 (1): 34. doi:10.2307/25161857. ISSN 0162-2897. JSTOR 25161857.

- ^ Dangerously Funny: The Uncensored Story of the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, by David Bianculli, Touchstone, 2009.

- ^ "Songwriter – Pete Seeger and Writing For Freedom". Peteseeger.net. July 28, 1976. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ Turton, Michael (August 14, 2011). "Surprise Lake Camp: Rich History, Big Presence". Highlands Current. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Bank, Justin (January 28, 2014). "Pete Seeger, Neil Diamond and me". Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Fellow Newport Board member Bruce Jackson writes, "Pete Seeger, more than any of the other board members, had a personal connection with Bob Dylan: it was he who [in 1962] had convinced the great Columbia A and R man John Hammond, famous for his work with jazz and blues musicians, to produce Dylan's eponymous first album, Bob Dylan. If anyone was responsible for Bob Dylan's presence on the Newport Stage [in 1965], it was Pete Seeger". See Bruce Jackson, The Story Is True: The Art and Meaning of Telling Stories (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008), p. 148.

- ^ John Szwed, Alan Lomax, 'The Man Who Recorded the World (Viking, 2010), p. 354. The Butterfield Blues Band, a new, integrated Chicago-based electric band, was the closer in an afternoon blues workshop entitled "Blues: Origins and Offshoots", hosted by Lomax, that had included African-American blues greats Willie Dixon, Son House, Memphis Slim, and a prison work group from Texas, along with bluegrass pioneer Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys. Lomax, upset that Butterfield's group had been shoehorned into his workshop, reportedly complained aloud about how long they took to set up their electrical equipment and introduced them with the words, "Now, let's find out if these guys can play at all." This infuriated Grossman (who was angling to manage the new group), and he responded by attacking Lomax physically. Michael Bloomfield stated, "Alan Lomax, the great folklorist and musicologist, gave us some kind of introduction that I didn't even hear, but Albert found it offensive. And Albert went upside his head. The next thing we knew, right in the middle of our show, Lomax and Grossman were kicking ass on the floor in the middle of thousands of people at the Newport Folk Festival. Tearing each other's clothes off. We had to pull 'em apart. We figured 'Albert, man, now there's a manager!'" quoted in Jan Mark Wolkin, Bill Keenom, and Carlos Santana's, Michael Bloomfield: If You Love These Blues (San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books), p. 102. See also Ronald D. Cohen's introduction to "Part III, The Folk Revival (1960s)" in Alan Lomax: Selected Writings, Ronald D. Cohen, ed. (London: Routledege), p. 192.

- ^ Rock critic Greil Marcus wrote: "Backstage, Peter Seeger and the great ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax attempted to cut the band's power cables with an axe." See Greil Marcus, Invisible Republic, the Story of the Basement Tapes [1998], republished in paperback as The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes (New York: Holt, 2001), p. 12. Marcus's apocryphal story was elaborated by Maria Muldaur and Paul Nelson in Martin Scorsese's film No Direction Home (2005)

- ^ David Kupfer, Longtime Passing: An interview with Pete Seeger Archived April 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Whole Earth magazine, Spring 2001. Accessed online October 16, 2007.

- ^ "Beans in My Ears". Sniff.numachi.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ Ingram, David (2008). 'My Dirty Stream : Pete Seeger, American Folk Music, and Environmental Protest', Popular Music Vol. 31, pp22. Routeledge Taylor & Francis Group. October 14, 2014

- ^ Gibson, Megan. "Songs of Peace and Protest: 6 Essential Cuts From Pete Seeger." Time.com, January 28, 2014. p.1 Business Source Complete. October 14, 2014.

- ^ Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, CBS, Season 2, Episode 1, September 10, 1967.

- ^ "How "Waist Deep in the Big Muddy" Finally Got on Network Television in 1968". Peteseeger.net. Archived from the original on August 5, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, CBS, Season 2, Episode 24, February 25, 1968.

- ^ See, for example, this PBS documentary Archived March 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine and this recording on YouTube.

- ^ Brown, Jim (Director) (2005). The Power of Song (DVD). Genius Products LLC. ISBN 1-59445-156-7.

- ^ Phạm, Tuyên. "Gảy đàn lên hỡi người bạn Mỹ – Câu chuyện sau khi bài hát ra đời". Nhạc sĩ Phạm Tuyên (in Vietnamese). Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Cohen, Ronald D.; Capaldi, James (December 16, 2013). The Pete Seeger Reader. Oxford University Press. p. 209. ISBN 9780199336128. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved October 9, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dickens, Hazel (2008). Working girl blues : the life and music of Hazel Dickens. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09097-4. OCLC 809471478. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ "Singalong Sanders Theater, 1980". Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Archived from the original on November 1, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Harrington, Gerry (January 31, 2014). "Movement afoot to name bridge after Pete Seeger". United Press International. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ a b David King Dunaway (2008), p. 103.

- ^ David T. Dellinger, From Yale to Jail: The Life Story of a Moral Dissenter (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993 ISBN 0-679-40591-7).

- ^ Where Have All the Flowers Gone: A Musical Autobiography, edited by Peter Blood (Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: A Sing Out Publication, 1993, 1997), page 22.

- ^ a b Daniel J. Wakin, "This Just In: Pete Seeger Denounced Stalin Over a Decade Ago" Archived October 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, September 1, 2007. Accessed October 16, 2007.

- ^ "The Old Left". The New York Times Magazine. January 22, 1995. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ Boaz, David (April 14, 2006). "Stalin's songbird". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2009.

- ^ Boaz's article is reprinted in his book, The Politics of Freedom (Washington, D.C.: The Cato Institute, 2008) pp. 283–84

- ^ Dunaway, How Can I Keep From Singing, p. 422.

- ^ Seeger turns on Uncle Joe Archived September 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, NewStatesMan, September 27, 2007.

- ^ Anderson, John (May 4, 1998). "The IRS Plays Tax and Consequences". Newsday. New York, New York. p. B7. Retrieved February 7, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "In New York, Thousands Protest a War Against Iraq". The Washington Post. February 15, 2003.

- ^ "How Can I Keep from Singing?": A Seeger Family Tribute Archived May 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. 2007 symposium and concert, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress (web presentation includes program, photographs, and webcasts).

- ^ a b Tommy Stevenson, "'This Land Is Your Land' Like Woody Wrote It" Archived February 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Truthout, January 19, 2009. Accessed February 3, 2014.

- ^ Maria Puente and Elysa Gardner, "Inauguration opening concert celebrates art of the possible", USA Today, January 19, 2008. Accessed January 20, 2009.

- ^ Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen at the inaugural concert at the Lincoln Memorial on YouTube. Accessed December 3, 2014.

- ^ Jennings, Jennifer. "Pete Seeger: The environmental side of his activism." Atlantic City Natural Health Examiner. January 28, 2014. Atlantic City Examiner. Accessed on October 5, 2014.

- ^ "Web site announcing Seeger's 90th birthday celebration". Seeger90.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ "Hudson River Sloop Clearwater". Clearwater.org. Archived from the original on October 2, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ "For Pete's Sake, Sing!-Ithaca, NY". Jimharpermusic.com. May 3, 2009. Archived from the original on April 28, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ "Yahoo". Upcoming.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ "Pete Seeger 90th birthday celebrations". Unionsong.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ Patrick Doyle, Video: Pete Seeger Debuts New BP Protest Song: Songwriter talks inspiration behind "God's Counting on Me, God's Counting on You", Rolling Stone online, July 26, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "Pete Seeger - God's Counting On Me, God's Counting On You (Sloop Mix) (feat. Lorre Wyatt & friends)". YouTube. November 5, 2012. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ "Civil Rights History Project". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (October 22, 2011). "Pete Seeger Leads Protesters in New York, on Foot and in Song". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2012.